Nike is a pioneer of sustainable infrastructure. Their 2016 Olympics campaign celebrated the diversity of the employees and supported female empowerment. In 2016, 48% of its global workforce were women and over half of its employees were minorities. Nike plans to run on 100% renewable energy by 2025. They are committed to transparency about working conditions in all their factories. But this was not always the case.

The Sweatshop Scandal

Since the 1990s Nike have been frequently accused of using sweatshops to cheaply produce their products. For a long time, they had a reputation of exploiting their workers so they would have to pay less to make their clothes and shoes, but a reversal in their attitude to sweatshops changed everything. This success is reflected in their changed reputation and improved sales figures. This shows that being an ethical company does not have to reduce corporate success.

Before the 1990s, Nike produced most of its products in Korea and Taiwan where required wages were low and labour was disorganised. Although there were no scandals, Nike took advantage of a situation where workers could not complain about being unfairly treated by a corporation. This attitude was to continue into the future and it is only relatively recently they have shown a significant change in their attitude for the better.

Once labour began to organise in these countries, Nike moved to Indonesia, China and Vietnam. Here they would be able to continue to produce at low costs and take advantages of available cheap labour. Problems started for them in 1991, when activist Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing their insufficient payment of workers and the poor conditions in factories. This report gained a lot of publicity and Nike responded by creating a factory code of conduct. But this did not lead to massive improvement.

Public Outcry

Ten years later, reputable newspapers like the Guardian were still reporting on how Nike had failed to make significant changes. They designed a code of conduct to ensure factory safety and better wages. But just one year later, Ballinger published another article in Harper magazine. It detailed how a Nike subcontractor paid workers in Indonesia less than 14 cents an hour in unsafe conditions.

All this attention had an impact on Nike’s reputation and sales. At the Barcelona Olympics, people protested against Nike’s poor working conditions. The issue received a lot of mainstream media attention on the issue and this continued for the next few years. Other scandals like revelations that Kathy Lee Gifford’s clothing was made by underpaid children strengthened public outrage.

Nike’s Initial Response

In 1996 they created a department to improve the lives and working conditions of factory workers. This was a response to public pressure to improve, and the demand for ethically sourced clothing. But as the next few years were to show, this was not the end of Nike’s sweatshop scandal.

From 1997, people became increasingly outraged at how Nike were ignoring complaints and continuing to increase their franchise. The media, including within sport, were no longer willing to believe Nike’s spokespeople. Nike could not ignore public demands for them to improve their working conditions. As the reported abuses increased in frequency and severity, Nike recruited a diplomat and ex-activist, Andrew Young. He had the job of examining their labour practices abroad and reporting back. His report was more favourable to Nike than many had expected, and so they published it quickly. But criticisms of Young’s work included failure to include low wages, solely using Nike interpreters, and Nike officials accompanying him everywhere. The media accused Nike of a cover-up. College students around the UK and the US staged mass protests throughout 1997.

How Nike Improved:

In May 1998, CEO Phil Knight said “The Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime, and arbitrary abuse”. Some believe this moment marks the shift in Nike’s attitude to use of slave labour. He announced Nike would increase the minimum age of its workers and continuously audit its factories. They would also adopt US clear air quality standards. From 2002-2004, they conducted 600 factory audits and revisited problem factories. Nike also allowed human rights groups and organisations to come into their factories and inspect them. This showed their new commitment to transparency and corporate ethics.

At Glass Clothing, transparency is foundational to our brand. We disclose information about each of our tailors right here on this website, so that you can know who is making your clothes.

In 2005, Nike produced a full list of its factories. In the same year it published a report acknowledging it still had to improve its Southeast Asian factories. This was a contrast from just eight years previously when activists accused them of abuse of workers there. From 2005 till the present day, it has been producing corporate social responsibility reports, as part of its commitment to continued transparency.

Their current company ethos is:

“when Nike creates meaningful change within our own company and within the communities that we influence, we make a positive difference in the world.”

Today, Nike had made huge improvements in the way they treat their workers. They have continued to be financially successful as a brand. This shows that it is possible to be both an ethical company and a profitable one.

Read about how Beyoncé’s ‘Ivy Park’ range fares in comparison

-

Green Silky Flares£30.00

Green Silky Flares£30.00 -

Purple Silky Flares£30.00

Purple Silky Flares£30.00 -

Aztec Straight Leg Cotton Trousers£20.00

Aztec Straight Leg Cotton Trousers£20.00 -

Swirly Cotton Trousers£20.00

Swirly Cotton Trousers£20.00 -

Black and White Straight Leg Trousers£20.00

Black and White Straight Leg Trousers£20.00 -

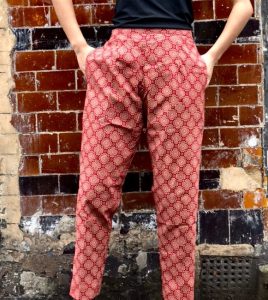

Red Straight Leg Trousers£20.00

Red Straight Leg Trousers£20.00 -

Flower Straight Leg Cotton Trousers£20.00

Flower Straight Leg Cotton Trousers£20.00